Caterpillars and butterflies

It’s 2024 and somehow we are still discussing Catholic teaching on slavery, despite nearly 500 years of consistent, clear papal increasing condemnations of slavery. In a post on Where Peter is, Paul Fahey relies too much on an unhelpful book by Jesuit Fr. Kellerman (“All Oppression Shall Cease: A History of Slavery, Abolitionism, and the Catholic Church”), and consequently makes a variety of claims that can be similarly unhelpful. Let’s go through some of them. [Quotes from Fahey’s post in italics.]

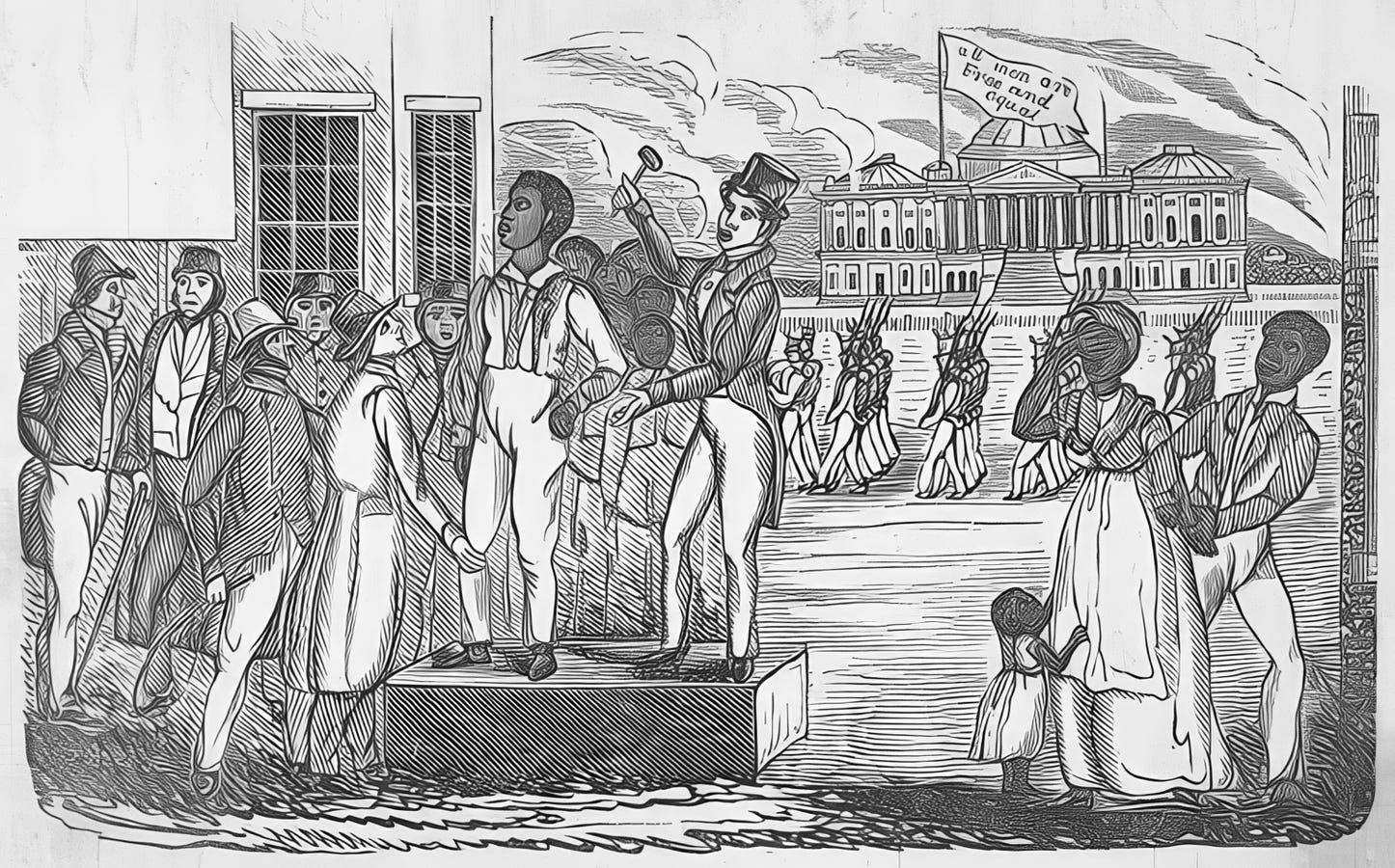

Forsyth [the US Secretary of State in 1840] had been publicly claiming that Pope Gregory XVI had condemned slavery in his 1839 Papal Bull In Supremo Apostolatus.

A lot of people had been asserting that condemnation was actually in the Apostolic Letter, including many Catholics outside the United States. It was a very reasonable understanding to reach.

Bishop England felt the need to correct the Secretary of State because Pope Gregory had not in fact condemned slavery itself, only the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Bishop England’s claim (shared with other American bishops) was, in essence: “No, no, no. The Pope is only condemning the trans-Atlantic trade in slaves, not the kind of domestic slavery and trade that we have in the south of the USA.” But the bishop never really properly explained why there was a difference that is significant.

As surprising as this may be for Catholics to hear now, Bishop England’s analysis of the Church’s teaching on slavery was not off base.

It was not totally off base, since it referred to some of the ways that slavery had been tolerated over the years. But it was problematic since it tended to negate what Pope Gregory XVI (and other Popes, over centuries) was saying: don’t make slaves, don’t separate them from their families, don’t keep them in slavery, don’t trade in slaves, don’t send them to other places, don’t teach or preach that it is lawful. And this was to be applied universally.

In the course of his letters, Bishop England drew from Scripture, Tradition, the natural law, and multiple historical examples of the Church tolerating and engaging in slavery to argue that slavery itself was not immoral …

Bishop England began a long series of sometimes quite detailed letters on slavery. In part, they described some common Catholic teaching about slavery and its various types. And they also went through some of the history of slavery. These letters stopped at a point when the Bishop went to Europe, became sick on the return, and did not fully recover before his death. So the letters don’t reach the point where the bishop could address the situation in the south of the USA in any detailed way. So it’s not clear exactly what the bishop might have said about that.

Bishop England’s claims that domestic slavery was not included in the Pope’s condemnation strike weakly. For example, he claims that domestic slavery doesn’t reduce anyone to slavery, because they are already slaves. And the condemnation of taking belongings from them doesn’t apply because, as domestic slaves, they have no property to be taken.

More significantly, the bishop establishes what the common Catholic teaching at the time described about the various ways that people can become slaves, but he doesn’t show that the slaves in the south actually fall into one of those categories. And they certainly don’t — they were originally captured to be slaves in violent raids by slavers, or in phony wars carried out to grab slaves for profit. So they could not be counted legitimately as slaves. Hence neither could their children. Which means all the “slaves” in the south of the US were unjustly held in slavery, even according to the common teaching that the bishop utilizes.

At the breaking-off of the series of letters, the bishop did remark that he was not friendly to slavery, but saw no way to get rid of it. (The angels of karma arranged that the first military action of the US Civil War happened in Bishop England’s diocese.) From reading some of the bishop’s life, I see him as being highly exemplary as a Catholic cleric. But his interpretation of the Pope’s Letter is forced out by some selective parsing.

So, it’s caterpillars and butterflies!

Caterpillars and butterflies?? What is that? Well, Paul Fahey’s post contains something which I think is extremely helpful. He refers to St. John Henry Newman’s metaphor of butterflies and caterpillars for the development and change of doctrine:

… this unity of type, characteristic as it is of faithful developments, must not be pressed to the extent of denying all variation, nay, considerable alteration of proportion and relation, as time goes on, in the parts or aspects of an idea. Great changes in outward appearance and internal harmony occur in the instance of the animal creation itself. The fledged bird differs much from its rudimental form in the egg. The butterfly is the development, but not in any sense the image, of the grub. [An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine: John Henry Newman]

Caterpillars and butterflies are developments of the same individual animal. They look very different, and can be described in unlike and contrasting ways. But they are expressions of the same individual animal. They have the same individual DNA that underlies them, and drives them.

In the case of doctrine, problems can arise when a doctrine starts to develop. The doctrinal change from caterpillar to butterfly starts, but those describing it may be locked into the idea that it is surely an ordinary caterpillar. Its butterfly features may be denied, even firmly denied, because they do not fit the caterpillar mold. This can go on for quite some time, with divisive and damaging results.

I think that this explains some of what Bishop England was doing. He did not have the goal of supporting slavery in the south, but of supporting Catholic teaching. But all he expected was a caterpillar. His actual practice in his diocese was of a butterfly. But for doctrine he could only describe what he expected to see — a doctrinal caterpillar.

I note that in a 1908 edition of Bishop England’s letters, edited by a bishop of Milwaukee, there is an editorial note:

The Church has never approved any form of slavery. In this matter her position has always been that of hostility […] When slavery presents itself as an existing fact which can be removed only at the great disadvantage of the slaves and to the detriment of the government, then the Pope declares existing conditions must be tolerated and the slaves are held to practice patience and forbearance. Prudent opposition to slavery, Leo declares, marks the history of the Church.

The continuing change towards a butterfly is apparent there.

If a caterpillar has no wings, but a butterfly does, this is not a contradiction, or a reversal. Someone might say: “Caterpillars just don’t have wings, so this butterfly is a contradictory reversal.” No, it is a development of the same animal.

And the reverse problem can exist: someone sees a doctrinal butterfly, and claims that caterpillars are just erroneous butterflies. No, it is the same animal expressed in different surroundings.

Owning a slave is not an intrinsic evil. If slavery is endemic to a social system, and beyond control, it can be a legitimate act to tolerate it. Perhaps it was often much, much too easily tolerated. But the arc over time was to reduce toleration to the point of getting rid of slavery. From caterpillar to butterfly.